The Cancer Survivors Network (CSN) is a peer support community for cancer patients, survivors, caregivers, families, and friends! CSN is a safe place to connect with others who share your interests and experiences.

Are we not all Gamblers playing in the Cancer Casino hoping 2 win Life's Lottery~but what if

This is not a “marriage counseling session”, but in all good marriages, there must be some “give and take”. That doesn’t mean one is always doing the “giving” and the other one just has to “take it”. I know of some marriages that are like that, and they’re not “happy”. Well, if that were money, I would like to be on the “receiving end”. But we’re talking about something that money can’t buy. Among those things would be “happiness” and a “cure for cancer!”

My husband and I have been married for 54 years. During that time, we’ve had to make difficult decisions just like other couples. It’s true that often “two heads really are better than one.” However, when it comes to making a decision about when to stop cancer treatments, the patient MUST be allowed to make the final decision, despite other’s desires to the contrary!

The 2016 Survival figures for William’s Stage “T3N1M0” diagnosis are 21% that he will possibly live for 5 years!

See Survival figures: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/esophaguscancer/detailedguide/esophagus-cancer-survival-rates-

Since I’ve now also been diagnosed with Ovarian Cancer, Stage IV in 2012, barring an absolute miracle, there will come a time when I will decide to “STOP MY TREATMENTS.” Currently there is no CURE for Peritoneal Carcinomatosis/Ovarian Cancer, Stage IV, just like there is no cure for Esophageal Cancer, Stage IV. According to stats for my type and stage are only 17% that I will survive for 5 years and I was diagnosed in November of 2012.

There are only palliative measures that can be taken that may include some type of surgery, radiation or chemotherapy. They are intended to give the patient more quality of life during this time of heartbreak for everyone involved. Although he is now into his 14th year of survival, as a Stage III EC patient, there is always the possibility of recurrence.

So here is a reprint of a MayoClinic article first published in 2006. (Condensed version is on the web today.) http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cancer/in-depth/cancer-treatment/art-20047350

I’m posting it here for anyone pondering the inevitable troubling question of when to STOP TREATMENTS, difficult as it is to face. JUST WHEN IS “ENOUGH ENOUGH”?

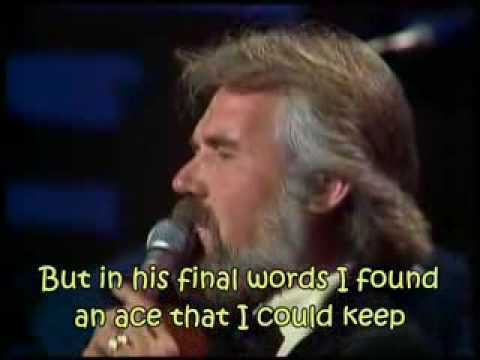

I often use the old Kenny Rogers’ song, The Gambler,  https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=azZr1cSu9-4to illustrate the decision that my husband and I both will have to make individually. We’ve got to pray to “know when to hold ‘em—when to fold ‘em—when to walk away—and when to run!”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=azZr1cSu9-4to illustrate the decision that my husband and I both will have to make individually. We’ve got to pray to “know when to hold ‘em—when to fold ‘em—when to walk away—and when to run!”

It occurs to me that we are all “gamblers” at the table in a “Cancer Casino”. The stakes are high. We’re all hoping to win the “Lottery of Life”!

Loretta

_________________________________________________________________________

STOPPING CANCER TREATMENT: DECIDING WHEN THE TIME IS RIGHT

Explore what it means to stop your cancer treatment — from what to consider when deciding, to what to expect once cancer treatment ends.

You've come a long way. You made it through your initial cancer diagnosis and the shock and fear that came with it. You've been through cancer treatment and the related side effects.

But for all you've overcome, if your cancer treatment isn't working as you and your doctor had hoped, you may face another tough step in your journey with cancer. You may eventually need to consider ending your cancer treatment.

As you and your doctor decide whether or not to stop your cancer treatment, take time to gather information and assess your goals. What you find might help you understand that stopping your cancer treatment isn't necessarily giving up. Rather, it's a way to gain more control over how you'll spend the rest of your life.

Changing your cancer treatment goals

When you were first diagnosed with cancer, you and your doctor probably discussed what sort of results you could hope for from your cancer treatment. You probably hoped that your cancer would be cured. But if your first line of cancer treatment didn't work as well as you had expected, you might have realized that your goal of a cure was no longer possible and that you needed to refocus your goal.

In life, whether dealing with cancer or anything else, goals aren't fixed and static. Goals must remain flexible and change with the circumstances. This is true when dealing with cancer. Though your first goal, reasonably, is one of cure, sometimes treatment doesn't go as you had hoped. Cure may no longer be a realistic option. Readjusting your goals can help you focus on those things you can still reasonably control.

Throughout your cancer treatment, three phases or goals of care exist. When you move from one phase to the next is up to you and your doctor.

The quest for a cure. During this phase you and your doctor hope to cure your cancer. You might be willing to put up with a large number of temporary cancer treatment side effects for the very large payoff — to be cured. If your cancer goes into remission, your goal might now be to maintain your health and make sure your cancer doesn't return.

-

Prolonging your life. If your cancer treatment doesn't proceed as expected, or if your cancer was diagnosed at a more advanced stage, the goal of being cured might not be realistic. If this is the case, a reasonable goal might be to control or shrink the cancer or prevent it from spreading. You might be willing to put up with some side effects of cancer treatment.

-

Comfort rather than cure. A time may come when further treatment has little chance of prolonging your life or of shrinking your cancer. In this setting, trying to achieve the highest possible quality of life is a reasonable goal. Side effects must be kept to a minimum because any benefits are likely to be small. At this point, you and your doctor work to keep you feeling as symptom-free as possible. You might now focus your goal on your family and relationships, rather than your cancer. This can be a time of great comfort and even personal growth.

Your treatment goals are never static, and you and your doctor should continually discuss your goals — slowly and gradually adjusting them based on your individual circumstances. The process is very gradual and evolves throughout the course of your illness.

Making the decision to end treatment

Making the transition to comfort and symptomatic (palliative) care can be a difficult choice. Talking about your decision with your doctor and your family might help you sort out your feelings. Some points you might want to discuss include:

What's your current condition? Ask your doctor to be honest about your cancer and its progression. And be honest with yourself. Denying that your cancer is progressing, while a natural response, might prevent you from being able to make the most of your time.

-

What's your treatment doing? Is it shrinking your tumor? Is it fighting your cancer? What benefits is it providing, if any? Think about the pros and cons of your treatment.

-

Why are you getting treatment? Is it to shrink the cancer and live longer? What are the chances of this happening? Is it to relieve a symptom, such as pain? Is it working for that symptom? Are you getting these treatments for yourself, or is it because someone in your life wants you to? Is there pressure from your family? Is it worth it? Many people with advanced cancer want to try every possible treatment, for fear they'll let down their loved ones if they don't. But sometimes, getting ineffective treatments only takes you away from your family and loved ones for longer periods of time.

-

What's the downside to treatment? What side effects do you experience? Are they mild or are they intolerable? To what extent does the treatment limit your ability to participate in the activities you enjoy? Consider your quality of life.

-

Is the downside worth it? For the benefit you're receiving from your treatment, are the side effects worth it?

-

What do you want for your future? Will continuing your treatment prevent you from taking part in those activities?

In your decision to end your treatment, take into consideration your religious beliefs and other personal values. Discussions with your religious adviser can help you focus your goals.

Discussing the end of your treatment with your doctor

In a perfect world, the decision of whether or not to end your treatment will be thoroughly discussed between you, your doctor and your loved ones. Your doctor would be sure of the potential benefits of your treatment. And you would be open with your doctor about your fears and hopes for your future.

In truth, your doctor might find your prognosis difficult to estimate, and you might be afraid to admit feelings of depression or anxiety. For this reason, it's important that you and your doctor have adequate time to ask each other questions and not be afraid to ask or answer difficult questions about your future.

Many times you and your doctor will agree with each other on whether to continue treatment. But in some cases, you might disagree.

When your doctor wants to end your treatment, but you don't

If your doctor approaches you about ending your cancer treatment, you might feel betrayed. You might feel like your doctor wants to give up on you. Maybe you've been denying the fact that your cancer treatment isn't working, and you aren't ready to accept the fact that it might be time to stop.

Know that your doctor has your best interests in mind, and listen to your doctor's reasoning. Ask questions. Be honest about how the thought of ending your treatment makes you feel. Just because your doctor suggests no longer treating your cancer, your doctor will always continue to treat you, to assure comfort and relieve symptoms to the best of his or her ability. Ask to see X-rays and other tests that show the progression of your cancer. This might help you better understand your doctor's opinion.

You might be reluctant to stop your treatment because you're afraid to lose control over your health. You might also equate ending treatment with giving up. But you can maintain both control and hope without the cancer treatment:

Maintaining control. Deciding you don't want any more cancer treatment is a form of control in and of itself. Taking away the treatment means you can have more time with friends and family without the side effects keeping you sidelined. You can control your pain so that you can have a better quality of life. And you still have control over several aspects of your own care, such as what you do and who you see.

-

Restoring hope. If until now hope has come from your expectation of a cure, then ending your treatment might seem like giving up hope. But you can draw hope from other places. Time with friends and family and the comfort your loved ones bring can provide hope, too. Terminally ill people often say that hope comes not from treatment, but through connections with others, spirituality and uplifting memories.

If, after discussing your treatment with your doctor and your family, you decide you don't want to stop your treatment, your doctor may be willing to continue treatment. However, if your doctor knows the treatment will only hurt you, he or she can refuse to treat you. If that happens, you can request a review of your case with the hospital or clinic management. Or you can get a second opinion from another doctor.

When you want to end your treatment, but your doctor doesn't agree

Sometimes pain and other side effects can make your cancer treatment unbearable. This may influence your decision to stop treatment — even if your treatment seems to be working. But pain and side effects can sometimes be remedied so that you're more comfortable as you go through your cancer treatment. Talk to your doctor about getting help for symptoms such as:

Pain. Without proper pain control, you might feel like abandoning your treatment before you've given it time to work. A number of solutions — from drugs to complementary therapies, such as meditation — can help you control your symptoms. Your doctor can't detect the severity of your pain, so it is up to you to speak up.

-

Anxiety. It's normal for you to be anxious about what is happening to your health. Anxiety about your future and your family's future — financial, emotional and otherwise — are completely normal. Medications might help you relieve your anxiety. But talking with your doctor or another health care professional can also help you sort out your feelings and provide relief.

-

Depression. Depression is common in people with cancer. But those feelings of hopelessness can contribute to your physical symptoms, making you think you're worse off than you really are. Medications are available for depression, and talking about your feelings can help. Physical signs and symptoms of depression, such as weight loss and fatigue, are difficult for your doctor to diagnose since they can also be caused by your cancer. So tell your doctor if you think you might have depression.

After these factors are controlled, you might be in a better frame of mind to make a decision about continuing your cancer treatment. Don't accept pain, anxiety and depression as part of your cancer — they can all be controlled to some extent most of the time.

If you simply don't want to continue treatment, that's OK. It's not a sign of weakness. When to stop treatment is a highly personal decision. You can always change your mind and restart your treatment if your doctor agrees.

In the end, it's your decision to make, but input from your doctor, other health care workers and your friends and family can be an important part of the decision-making process.

Telling your family and friends

If you decide to end your cancer treatment, be honest and open with your family and friends when telling them. Talking about your feelings can be therapeutic. It can also help your friends and family come to terms with your decision to end treatment. They'll better understand what they can do to help you and how you want them to behave toward you. You might prefer to keep your feelings to yourself, and that's OK too.

It's possible that your friends and family might not understand your decision because of fears about your future or theirs. Talking about your decision to end your treatment and your change in goals might help them overcome these fears.

If you have difficulty talking with your friends and family or if they have difficulty accepting your decision, talk to someone trained in counseling, such as a nurse, social worker, psychologist or a member of the clergy. That person might have ideas for you to make talking with your friends and family easier.

Your friends and family may just need time to adjust to your decision. Let them know you want them close and still need their support.

Talk with your family about your wishes for the future — called advance directives. Discuss whether you'd want to be kept alive if machines were breathing for you. Appoint someone to make health care decisions for you if you were to become incapacitated.

What to expect after your treatment ends

If you decide to end your treatment, it doesn't mean you'll stop being cared for by doctors and nurses. You and your doctor will discuss your options. You might have a loved one or friend who wants to help take care of you. Or you might decide to use a home nursing service.

No matter what you choose, you'll still have regular checkups to make sure your pain is kept at bay and that you're comfortable. Your doctor might have you seen by another doctor who specializes in palliative care — a doctor whose main focus is to make you comfortable, not cure you.

Stopping your treatment doesn't mean you'll die immediately. After you end treatment, you could still be active and care for yourself for many months. It's also possible your health could deteriorate rapidly. How long you'll live after ending your treatment will vary depending on the type and stage of your cancer, as well as other health problems you may have.

Whether you want to stay at home is up to you and will depend on the level of care you need. You might feel more comfortable in a hospital or nursing home with doctors and nurses nearby at all times. Or you might prefer the comfort of your home with a nurse to check in on you every day. You might choose a hospice program, which is designed for people who generally aren't expected to live more than six months.

MORE TIME FOR WHAT MATTERS

When ending treatment makes you pain-free and more able to participate in various daily activities, you might find you have more time for friends and family. Being able to be cared for at home might mean you could keep up with hobbies or activities that make you happy.

(By Mayo Clinic - Feb. 20, 2006) (Permission granted for noncommercial personal use only)

Comments

-

I just had this discussion

I just had this discussion with my nurse advocate at my insurance company this morning. Unfortunately, I do not feel like I am a partner with my health care professionals especially my oncologists. Hopefully when I get a different insurance plan on January 1st, I will find a better one. I am certainly not at this point yet but have made very specific plans when and if the cancer returns.

Love,

Eldri

Stage II, Grade 3 UPSC Endometrial Cancer

Discussion Boards

- All Discussion Boards

- 6 Cancer Survivors Network Information

- 6 Welcome to CSN

- 122.6K Cancer specific

- 2.8K Anal Cancer

- 457 Bladder Cancer

- 312 Bone Cancers

- 1.7K Brain Cancer

- 28.6K Breast Cancer

- 407 Childhood Cancers

- 28K Colorectal Cancer

- 4.6K Esophageal Cancer

- 1.2K Gynecological Cancers (other than ovarian and uterine)

- 13.1K Head and Neck Cancer

- 6.4K Kidney Cancer

- 683 Leukemia

- 804 Liver Cancer

- 4.2K Lung Cancer

- 5.1K Lymphoma (Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin)

- 242 Multiple Myeloma

- 7.2K Ovarian Cancer

- 70 Pancreatic Cancer

- 493 Peritoneal Cancer

- 5.6K Prostate Cancer

- 1.2K Rare and Other Cancers

- 544 Sarcoma

- 744 Skin Cancer

- 661 Stomach Cancer

- 193 Testicular Cancer

- 1.5K Thyroid Cancer

- 5.9K Uterine/Endometrial Cancer

- 6.4K Lifestyle Discussion Boards